The following from the Journal D'Agriculture Tropicale Paris France contains so much valuable information that I have translated it entirely for the information of readers.

"THE CACTUS AS A FOOD FOR DOMESTIC ANIMALS"

The known facts of the cultivation and use of the Plant in Algiers and Tunis-the thorny cactus and the cactus without thorns-Leaves (Raquettes) or fruits? The proposed international investigation-questions. By M. A. Jehanne.

The Cactus or Indian Fig has a very extensive range. It is to be found today in America from California, Texas and Florida to the Argentine Republic. It is found again in Madagascar, at Cape Town in Australia and in the Mediterranean basin, especially in Italy, Spain, Algiers and Tunis. In these last two countries stalks (raquettes) are sometimes used as food for domestic animals, and its fruits are much esteemed by the people. Still more is it prized in Italy where the "Indian Fig" cultivated for its fruit, has reached a high degree of perfection.

It is very desirable that the cactus should take as soon as possible an important place in the agricultural regions where prolonged droughts make it very difficult to furnish stock with juicy food where it is almost indispensable during periods of great heat. Many of our colonies would find it greatly to their advantage to cultivate the cactus; and every possible attempt should be encouraged to disseminate it and perfect its culture in Senegal, Sudan, the greater part of Madagascar, in some districts of New Caledonia and Indo China.

The culture of the cactus presents, in fact, some great advantages in the dry regions.

The cactus has a rare hardiness. In Tunis and Algiers it is to be found, to some extent, every-where, in the plains as well as on the driest hills. In dry earth, on the slopes of hills, in situations most unfavorable to almost all cultivated plants it develops satisfactorily. It endures the highest temperature; although it loses part of its moisture in the dry season it quickly regains it when the first rains come. Again it grows vigorously in the mountain thickets at the edge of the zone of the olive where snow and frost abound. But notwithstanding its great powers of vegetation no region in Tunis or Algiers has ever had cause to complain of the encroachment on cultivated lands by this cactus, which is like that produced in Australia, Madras, Cape Town, etc.

The planting and cultivating of the cactus is extremely easy, and the expense entailed is not very great. In Algiers and Tunis, in starting a plantation, it is only necessary to place single leaves (raquettes), or better single leaves with two shoots, in a series of holes on strips of plowed earth separated by spaces, from which it is not necessary to remove the native vegetation. A little manure is placed in the bottom of the hole, the cutting placed on top, and some earth is heaped up at the base. After that one need only heap up the earth the second year and again the third. There is no need of weeding as the cactus defends itself against foreign plants. The total expense of establishing and maintaining a plantation would not much exceed 100 to 150 francs per hectare- about two acres-$10.00 to $15.00 per acre.)

Even if the cactus yielded no product of direct utility, yet it would, on account of its great hardiness and rapidity of increase, perform a very distinct function in preventing the rain from carrying away superficial layers of soil from barren slopes which the rain waters would surely carry to the sea where would be wasted uselessly this most precious portion of the earth's crust, the portion most rich in elements of fertility. Moreover the cactus facilitates the penetration of the earth by waters which reappear below in the form of springs. It is impossible to repeat too often that, in such countries as Tunis and Algiers where frequently torrential rains are separated by long seasons of drought, too great effort cannot be made to retain in the ground as much as possible of this water which ordinarily trickles away without benefit to agriculture over the numerous barren slopes. It is not necessary to wait until it forms into rivulets before trying to catch it. It is much sooner than this, when the water has as yet formed merely liquid threads which the tiniest obstacle can divert that the effort should be made to make it penetrate the soil. The cactus, planted on cleared strips, worked out according to the contour of the surface, may be advantageously employed to this end.

But, as we have just said, the cactus does afford products of great importance in the feeding of stock. The Journal Tropicale D'Agriculture has insisted upon this point and has been quite right in so doing.

In Tunis the stalks destined for stock can be harvested as early as the fourth year and that too without any expense in the maintenance of the plantation. Moreover this yield may continue almost fixed for a very long time as has been observed in the case of cactus plantations as much as fifty years old yet still vigorous and productive. Finally this food can be used during the period when green food is most scarce, i.e., from July to November in North Africa.

This brief review of the services of the cactus is sufficient to prove that it is invaluable to dry regions. And yet, in spite of all its advantages, its area of culture is not in accord with the use that might be made of it. This state of affairs is perhaps due to some difficulties which could probably be overcome, that are presented by the attempt to employ the varieties actually known.

The varieties of cactus, truly very numerous but not thoroughly studied may be grouped from the agricultural point of view into two groups: (1) The varieties with thorns (Kermous en Nessara, of the Algeriens; Hendi Roumi, des Tunisiens) and the varieties without thorns (Hendi Ameles of the Ttmisiens). This is a distinction based solely on the presence or absence of thorns on all parts of the plant. The stalks (raquettes) of the thorny cactus are used only with great difficulty as a food for stock. It sometimes happens, however, that stock will eat them when pressed by hunger or by the necessity of finding juicy food in the warm days of spring. But the cropping of this food is rendered difficult on account of the thorns which, moreover, are sometimes the cause of serious inflammation of the digestive organs.

In order to obviate this inconvenience one may expose the stalks to a quick fire; the thorns burn readily. Nevertheless the fact remains that when the stalks are intended to be used in the stock barns as in mixing with other foods, the gathering and feeding of them is managed only with great difficulty and not without entailing some risk of injury to the workmen who handle them. Moreover it has been observed in Texas that in burning the thorns slight blisters are produced which result in a change in the food substance of the stalk which is capable of causing grave gastric troubles in the animals that consume the food thus treated.

The fruits of the thorned cactus present the same difficulties as the stalks. One may eliminate the thorns from the fruits also by means of a quick fire. The gathering of the fruits, which often grow high, is particularly difficult and requires considerable labor. This fruit must be consumed immediately as it begins to ferment a short time after it is detached from the stock: Fermentation is the more rapid perhaps because the season of maturity is that of great heat. They mature, in fact, during the summer season, beginning at the end of July and lasting not much more than two months. And at the time of the most abundant production of fruit the scarcity of fodder has not as yet begun to make its sad results so cruelly apparent.

The cactus without spines does not present certain of the difficulties of the foregoing varieties. But, on the other hand, in order to establish a plantation, it is necessary to enclose the field in order to keep the spineless plants from being devoured by stock, whence arises an expense quite large in comparison with the other expenses of establishing a plantation. Moreover, it has been observed, at least in North America, that the yield of fruits from the thornless cactus was less than that of the spined variety. One frequently sees a spined and a spineless cactus growing side by side, the former bearing 12 to 15 fruits to each leaf, the latter only 3 or 4.

In addition to the above disadvantages the cactus stalk is often considered as of no food value or of very little since its proportion of water is 93 per cent. But in spite of this great proportion of water, the stalk can still be of service in the feeding of stock. Different analyses* have shown that it has some nutritive value and also that there are numerous proofs of good results obtained by the mixture of cactus stalks and other food mixtures.

Mr. Ch. Riviere (Ch. Riviere, The Thornless Cactus. Review of Colonial Agriculture 1899, p. 136,) reports that Mr. Couput recommended a method employed in Algiers for more than fifty years which consists in feeding beef cattle, milk cows, goats, etc., with thornless cactus and chopped straw mixed in equal parts. He points out that 150 lbs. of cactus stalks added to 45 lbs. of ground Carob beans slightly fermented and 25 lbs. of grain or oil cake make a good fattening and appetizing food for the larger cattle, especially for milk cows.

A stock raiser of Texas has also shown that for the fattening of young steers he used, with good results, 60 lbs. of cactus and 6 lbs. of cottonseed meal per head each day.

M. Grandeautt in a clever article already cited believes that nothing could be easier than to com-pose a food mixture, equal at least to good wild prairie grass and much superior to the richest grain straw, by adding to the cactus the leaves or twigs of the native vegetation which abounds on the uncultivated lands of the North of the Province of Tunis. He announces that mixed in equal weights with cactus stalks, the leaves of the strawberry tree, the twigs of the mastic tree and the branches of cytisus form a food superior to prairie grass. And he adds that several years ago, during the scarcity of fodder, M. Lang, overseer of the Great Dormain in Corsica introduced very successfully into the rations of his cattle a mixture of leaves of the strawberry tree (arbousier) and cactus stalks. He states that the cattle and horses ate it greedily. He has called attention to the favorable results of using the leaves of the strawberry tree as a fattener, which is not surprising considering their heavy component of starchy matter.

In view of the small amount of nutritive matter in the cactus, it has been asked if it were not better to use the fruits in preference to the stalks. It is admittedly very difficult to obtain a crop of stalks and also of fruit the same year and to utilize them at the season when forage is most scarce. A priori, M. Grandeau, is inclined to sacrifice the fruit to obtain the stalks for stock food; on the one hand because of the stalks' richness in water which makes it a valuable food during the dry season. On the other hand because it seems better adapted for the coarse mixtures suited to the bovine species.

On the contrary, M. Bourdeyy, is convinced that the use of the fruit is of more advantage than the stalks. In the analysis of Wolf, the Indian Fig is given the following composition:

| Dry material | 21.60 per cent |

| Woody material | 3.70 per cent |

| Protein | 0.59 per cent |

| Fatty matter | 1.80 per cent |

| Sugar | 14.00 per cent |

It should therefore be a very good forage plant of a nutritive value inferior to that of the potato or the Jerusalem artichoke but superior to that of the carrot or the beet. An analysis made in the Chemical Laboratory of the Department of Agriculture and Commerce of Tunis, has given results different from those of Wolf and according to which the nutritive value of the Prickly Pear would be appreciably less than that stated by Wolf. It may be inferred from this disparity of analysis that the different varieties of cactus have different compositions. There is room therefore to make a careful choice among the varieties

M. Bourde, after his study of the cactus, was the originator of an inquiry to find a variety of cactus which would produce regularly the yield of fruit, sometimes cited, of 20,000 kilograms to the acre, and which would retain the nutritive value indicated by Wolf. Such a research deserves the most careful consideration. For the results it may bring may contribute greatly to the solution of the difficult problem of feeding stock in regions where prolonged dry seasons prevail, a problem of which the importance to most of our colonies is known to everyone.

In place of limiting the problem of the employment of the cactus as a stock food to the consideration of the thornless varieties alone, it would perhaps be better to extend the research to cover the following points:

- Are there any regions where the thorned cactus is used practically in feeding stock? The same question as to cactus without thorns. In the case of the use of the thorned cactus, has anyone ever succeeded in completely overcoming the various difficulties arising from the presence of the thorns?

- Have any differences in hardiness been ob-served between the varieties with thorns and those without thorns? Also have differences in yield of the stalks and the fruits been observed? Are there differences in nutritive value between the stalks and the fruits of the different varieties? (In each case to define the differences.)

- What is the method of handling the cactus (stalks or fruits or both) which gives the best results from the points of view of feeding stock with the different aims that one may have (vii., breeding, working fattening, etc.)? To find out the forage mixture containing cactus which gives satisfaction in each of the above cases.

- Does there exist a thornless variety productive e enough and with fruits rich enough to make its culture immediately profitable? If it does not exit, has anyone anywhere made attempts to create it? A. JEH ANNE.

Tunis, Jan. 15, 1904

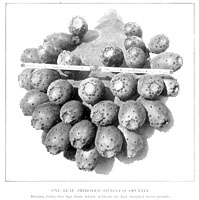

PICKLY PEARS

[From Law's Grocers' Manual, London, England]

These are also known among plant lovers as Barbary Figs, Indian Figs, etc. They are the pear-shaped fruit of Opuntia tuna, a species of cactus. There are several varieties, native of South America and Mexico, now grown in the West Indies, Brazil, Florida, etc., but we receive most from Spain, Algeria, and other parts of Africa.

The wild varieties, although sweet, nutritive, juicy and invaluable in dry, hot, sandy countries, are generally flat and insipid to the taste. They abound in India, around Delhi, and were introduced into the Deccan by a Sirdar of the old Poona Court to be grown as a defense against military attacks.

The plants are also found a convenient hedge between fields or a fence about farmsteads, being at once impenetrable and uninflammable. The jointed, juicy, columnar stems of the plant form an excellent fodder for cattle, so do the leaves and fruit, although both leaves and fruit are armed with minute but very sharp and stinging prickles, which produce violent inflammation and swelling, like nettles. Sheep and cattle are very fond of this fruit, and soon get fat on it. In some parts of Africa the leaves are chopped and fed to ostriches and dairy cows during droughts and periods of scarcity. The plant thrives best on barren spots, rocky shelves, etc., where nothing else will grow-and is, therefore, of great value in restoring vast tracts of desert lands to cultivation, although owing to the vitality of its hard seeds, it is difficult to extirpate it when it once spreads. * * *

The proper way to peel the fruit is to hold it on a fork or skewer while you cut it open and remove the skin. They should never be touched by the hand, or they will sting like nettles.

The White Prickly Pear is noted for its agreeable acid flavor. The Yellow is rather sweeter; the Crimson, both large and small, are quite sweet; the Japona is so called by reason of its costive effect when eaten in large quantities; the Pelona (a naked variety, almost destitute of the objectionable prickles) is a great forage plant, and will grow almost in any warm climate if not very damp. The leaves are very large and thick, averaging about 8 lbs. each.

Another variety, the Xoconostle, makes a most delicious preserve, its peculiar "foreign" flavor being much esteemed, and quite as distinct from other jams as Indian chutney is from English pickles.

In practice pear is very seldom fed alone. Even during the severest drought cattle are able to pick up some old grass and get a little browse from the abundance of brush that exists throughout the pear region. It is seldom that the Texas rancher feeds it without some cottonseed meal, although the cactus of southwestern Colorado has usually been fed alone.

SINGED CACTI AS FORAGE

[From The Pacific Rural Press]

During the periods of long drought, to which the southwestern United States is liable, range cattle frequently browse upon various species of cacti common to the region.

The Arizona Experiment Station has reported the results of studies regarding the utility of this class of forage plants, particularly after the spines have been removed by burning by means of a prickly pear burner-that is, a gasoline torch, similar in principle to that which plumbers use. The spines of about 300 plants of the species of cacti commonly found in the neighborhood of the station, including prickly pears, chollas, etc., were singed, the spines being burned off at intervals for about ten days.

The first 50 plants that were singed were literally devoured by the stock, the

|

Conservative estimates indicate that from 7,000 to 11,000 lbs. of cactus forage can be prepared daily in this way at a cost of $2.40, which represents eight gallons of gasoline at 30cents per gal. The amount of water in this forage, as determined in the experiment station chemical laboratory, is approximately 75 to 80 per cent, leaving 20 to 25 per cent, or 1,600 to 2,500 lbs. of solid matter for the day's work.

Cacti have been analyzed at the Arizona and California Experiment Stations. Carbohydrates constitute the principal nutritive material in the dry matter of the cacti. The amount of protein present, as in the case with most green fodders, is small. The ash content was found to be high, "suggesting an explanation of the purgative effect of this forage upon cattle."

In the above estimate no account has been taken of the possible expense of one extra man to operate the burner, since ordinarily this work can be done with the paid help already at hand. The relative value of this class of forage is as yet in question. The expense and trouble of burning, however, will be amply justified if range stock can be successfully carried over periods of extreme shortage. The large amount of water in this forage is of no small value to thirsty, starving cattle, doubtless enabling them to feed much farther from their watering places than they could otherwise do.

J. J. Thornber, who carried on the Arizona investigations, states that in using a gasoline torch for singeing cacti, the tank should be suspended from the shoulder in such a way that the end which supplies the gasoline to the burner is always down. As a matter of economy it will be found desirable to maintain a good pressure of air in the tank, and to avoid using the burner in a brisk or even a moderate breeze, since one-third more gasoline is then required.

In connection with an extended study of Prickly Pear and other cacti as food for stock, carried on by D. Griffiths, of the Bureau of Plant Industry of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, data regarding different methods of singeing cacti, the use of the singed material as a feeding stuff, and other questions were considered.

The most prevalent practice in southeastern Colorado, according to Dr. Griffiths, consists in singeing the spines over a brush fire.

This operation is practicable where there is considerable brush or wood conveniently situated, but it has many disadvantages. The plants are collected and hauled to some convenient place cohere the fire is built. A brisk fire will remove the spines from one side of the joints almost instantly. It is then necessary to turn the plants over and burn them again on the other side. Some careful feeders often leave the plant on the fire until much of the outside has turned black from the heat, in order to insure the removal of the short as well as the long spines. Others exercise less care, and simply allow the flames to pass over the plant, burning off only the distal half or more of the long spines and leaving practically all of the short ones for the cattle to contend with. It often happens that the fuel used is greasewood (Sarcobatus vermiculatus) or shad scale (Atriplex caenescens), the young shoots of which are of greater nutritive value than the pear itself. On the arroyos and washes dead cottonwood timber is used, while in many localities juniper furnishes the fuel.

This is the most primitive method of feeding and one which has been practiced in Texas since before the Civil War, and is still extensively employed not only in Texas, but also in old Mexico, where singeing the thorns with brush is about the only method employed in feeding prickly pear and other species of cacti.

The use of the gasoline torch for singeing cacti, it is stated, originated in Texas, and is commonly practiced on the range. It is economical from the standpoint of the labor involved, as well as from the quality of the feed.

The process consists in passing a hot-blast flame over the surface of the plant, which can be very quickly done at small expense. The spines them-selves are dry and inflammable. In many species one-half or two-thirds of them will burn off by touching a match to them at the lower part of the trunk. The ease with which they are removed depends upon the condition of the atmosphere, the age of the joints, and the number of the spines. A large number of spines is often an advantage when singeing is to be practiced, because the spines burn better when they are abundant. The instrument used for this purpose is a modified plumber's torch. Any other convenient torch that gives a good flame can be employed, the efficiency depending upon the lightness of the machine and the ease with which the innermost parts of the cactus plants can be reached by the flame.

Cattle brought up in (prickly) pear pastures do not have to be taught to eat pear. They take to the feed very naturally. After a day or two of feeding the sound of the pear burners or the sight of smoke when pear is burned with brush, brings the whole herd to the spot immediately, and they follow the operator closely all day long, grazing the pear to the ground-old woody stems and all -if the supply that the operator can furnish is short.

Pear, when burned, scours cattle much worse than when it is simply scorched enough to take the thorns off. * * * Burning with a pear burner tends to kill out the pear if close pasturing is practiced afterward.

"Cactus Fed Beef"

[From The Butchers' and Stock-Growers' Journal]

In our issue for March 31st last, under the above caption, appeared an article showing that cacti in general and the prickly pear in particular had been used as a food for stock, and that cactus "fed beef" had already been marketed. Further that that wizard of the vegetable and floral kingdoms, Luther Burbank, had succeeded in developing a cactus without spines and free from acid juice, and more nutritious than the prickly pear.

We have received a very interesting letter from L. Von Tempsky, manager of the Haleakala Ranch Company. Mlakawao, Maui, T. H., confirming all such statements and giving valuable particulars regarding the use of the prickly pear as cattle and hog food. As will be seen, he states that there is a wild spineless cactus in Maui, which is news to us. While it may not possess all the virtues of the Burbank variety, it is certainly worthy of investigation and propagation. When the right kind of cactus has been obtained there will not be an acre of arid land in California and Arizona which will not be open to cactus cultivation and sustain its share of cattle. This matter is of growing importance, and the letter which is given below, will be read with much interest.

Haleakala Ranch, Makawao, Maui, T. H., April 17, 1905. Editor Butchers' and Stock-Growers' Journal)

I read with much interest in your issue of the 30th ultimo the article on "Cactus Fed Beef."

On this ranch we have one paddock of twelve hundred acres covered very thickly with cactus or prickly pear; there is also a slight growth of Bermuda grass growing. In this paddock are pastured all the year round, four hundred head of cattle, and about seven hundred hogs. The cattle only get water when it rains, that is, during the months of December and January; the other ten months they subsist entirely and solely on the fruit and young leaves of the cactus which they help themselves to. It is a remarkable fact that during the dry months of the year, we get more fat cattle percent from that paddock than from any of the others.

I consider cattle fed on cactus like these are, to have as fine flavored beef as any I have tasted in San Francisco or New Zealand.

The hogs, with the exception of a light daily ration of corn, fed to keep them tame, live exclusively on the young leaves and fruit, which are fed to them by herders, and thrive wonderfully. This cactus has a brick red flower, and a most beautiful claret colored fruit, which the Hawaiians ferment, and distil into a very powerful spirit known as "Okolehoa."

The first stomach of cattle eating this fruit is inedible owing to the myriads of small spines which adhere to the walls. I have never known an animal to die from the effects of this.

We have also here the spineless cactus, which is identical with the before mentioned except for the lack of thorns. Where it came from I don't know.

L. VON TEMPSKY, Manager Haleakala Ranch Co.

CACTUS FOR STOCK

[From The California Cultivator]

Many readers have read about the cactus or Prickly Pear, which grows on the Great American Desert. This cactus is protected by sharp, stout thorns, which cut like a knife and remain painfully in the wound. Cattle are sometimes seen with these fearful thorns sticking in their lips and tongue, which indicates that in their thirst or hunger they are willing even to brave these weapons in order to secure the cactus. No one could expect them to furnish a Thanksgiving dinner for stock. The Desert is well covered with them in many places, and scientists and practical cattlemen alike believe that if the spines could be removed the plant would offer fair food for stock. Various plans were tried for getting rid of the spines. The latest is found in a bulletin issued by the Arizona Station. It appears that a special burner for singeing cactus has been invented. It uses gasoline and gives a fierce heat and flame. The operator carries the gasoline tank on a strap fitted over his shoulder. The burner is supplied from this tank by means of a tube and can be held out at arm's length on the end of a rod. This appliance is moved over the cactus, so that the spiner or teeth are singed off, the whole thing being much like a gasoline torch often used by plumbers. It was found that from 7,000 to 11,000 pounds of cactus forage could be singed in one day at a cost of about $2.40. The cattle ate the fodder greedily after the spines were burned off; in fact they devoured the plants down to the ground at the risk of destroying them, so that now only half of the plant is singed at one time. This leaves half uneaten and the other part grows up again. The cactus plant contains on an average over 75 per cent of water and over six per cent of protein, which latter is about half the amount found in a sample of wheat bran. It would seem as though Nature had placed this food before cattle while in her most bountiful mood, and then in a moment of caprice has put on the spines to keep them away from it. Thus simple operation of singeing provides a new and excellent forage for range cattle.

CACTUS FEEDING

[From The Southern Cultivator]

Out in the cactus section where they feed the spiny cactus they have several ways of making the thorny stuff possible for the stock to eat it. The least troublesome way is to go around the bunches with a long handled knife and trim the edges of the lobes and then the cattle can nibble at it very gingerly, for while the outer rim is taken off there are hundreds of bristling spines to contend with and stick fast in the tender mouth. Mr. Johns of Colorado steams the cactus and this softens them so they are not so dangerous. In Texas they have cutting machines and generally when they cut the cactus up they do not burn the spines off first, but where they do not cut it they singe them off with brush fires, not an inexpensive experiment in a country where fuel is scarce. So the problem is to finally raise a spineless variety that will re-quire no singeing, cutting or steaming. A cow will eat 70 pounds of the prepared cactus in a day and it keeps up the flow of milk.

TRYING TO GET CACTUS' SECRET

Professor endeavoring to discover from whence cometh its water.

[From The Monterey (Mexico) News]

Professor A. F. Collyer, of Massachusetts, an authority on cacti and other desert plants, is in Monterey now and will remain here several days. Professor Collyer has been in Mexico about six weeks and has visited many different localities in search of rare specimens of the cacti. He has slipped several lots to the United States and stated yesterday that he expected to make some new discoveries before he reached the border at Eagle Pass. The professor is accompanied by two assistants and the driver of the stage in which they are traveling. Most of the distance is covered afoot, however, as all three of the parties are making researches for the benefit of science. Many curious discoveries have been made by the warty and it is probable that most of them will find their way to the various botanical gardens throughout the United States.

In speaking of his profession, for Professor Collyer says the study of the cactus plant is a profession: "Mexico" offers a broader field than all the rest of the world," began the scientist. "There are more varieties of the plant in this country than any- where else. Few people realize that the cactus is distinctly an American plant. It grows in North, Central and South America, but the mountains and deserts of the rest of the world know nothing of this peculiar plant.

Another point advanced by Professor Collyer was that all desert cacti had thorns or spines, which perhaps told the history of their being so plentiful in some parts of the world. Were it not for these thorns and spines, the plants would have long ago been destroyed or devoured by man or animal. There are some species of cacti that are edible. The Indians of the southwestern part of the United States eat certain kinds of cacti and the fruits of many varieties are delicious. Here in Monterey one can get all sorts of cacti fruits offered for sale by the vendors and market merchants.

Scientists are endeavoring to discover how to make the cactus an animal food. When this discovery is made it will mean much to the cattlemen of Mexico as well as those of the United States. Another thing is, where does the cactus get the water that goes to make up its substance?

"This question is one that as yet has never been studied scientifically until recent years. Scientists are now making extensive researches and once the facts become known, it will naturally be of great benefit to the Americans of whatever country. There are some of these plants that contain as much as 80 percent water and still they are to be found miles and hundreds of miles away from rivers, creeks and wells, nor have any rains visited the sections in modern times. Now the question is, where does this plant get the water? It may draw it from the clouds or from the earth and this is just the information we are seeking. I hope that the scientific world will have these facts in its possession before another year rolls by."

The party on leaving here today or tomorrow will go in a northern direction and expect to reach the border in a couple of months. They are taking their time and pitch camp whenever they feel so inclined. It is probable that after crossing the river at Eagle Pass the party will continue on its way to Arizona or New Mexico where additional searches will be made.

Professor Collyer is writing several articles on the cactus plant, which should prove interesting reading when completed.

CACTUS A POSSIBLE SOURCE OF WEALTH

From The Sacramento (California) Bee.,

The demand for ethyl alcohol for industrial uses is expected to be very large, now that the heavy internal tax has been removed on that product when made unfit for drinking purposes by the addition of a little methyl or wood alcohol and benzene. This denatured alcohol, as it is termed, may be used for fuel purposes and for lighting as in Europe. It serves to run automobile and engines of all kinds, and in the manufactures has a hundred uses. The extent to which it may be employed in this country will depend largely on the cost of making it as compared with gasoline, and estimates are current that under the requirements imposed by Congress it can scarcely be retailed at less than 40 cents a gallon.

Ethyl alcohol may be made from many sub-stance`, and one of them is the common cactus of the deserts. A bulletin issued by the New Mexico Agricultural Experiment Station gives some interesting particulars in this regard. It relates the experience of a man in New Mexico who cultivated cactus for a number of years, to see what results could be had. He estimated that if the plant were cultivated on 1,000 acres without harvesting for three years, 100 tons could be obtained indefinitely from that area every day in the year, making 73,000 pounds per acre annually.

That the millions of acres of desert land overgrown with cactus may be made a source of large revenue seems almost incredible, but stranger things have happened. Unless Burbank be badly mistaken, the spineless cactus is destined to become one of the most useful of plants, furnishing abundance of food for man and beast in regions which have been regarded as too sterile and desolate for any form of stock-raising or farming. And the profitable conversion of the common form of the plant into alcohol seems even better assured.

TO LOCATE A CACTI GARDEN

Government Expert is Here and may Recommend Riverside for Cactus Experiment Station- to Develop Spineless Cacti.

[From The Riverside Press]

David Griffith, who is connected with the National Department of Agriculture, is in the city with a view to possibly locating here a cacti experiment station. It is the purpose of the government to locate in California an experiment station to develop the prickly pear into a plant of commercial value as a feed for stock. The government has already established stations at San Antonio, Texas, Organ Mountains, New Mexico, and a third near Tucson.

Mr. Griffith will make tests of the thornless cacti developed by Burbank. Mr. Griffith says that all spineless cacti are less hardy than the thorny varieties and it is to breed a hardy variety that lie will bend his energies.z

CACTUS CULTURE AN INDUSTRY

[George P. Hall in The Fruit World]

"When the laws are perfected so the trust will not have the advantage, the raising of cactus will be an industry of no small magnitude, and the spineless will have the decided preference, in all cactus-growing sections of our State, and a well -stocked cactus farm is one of the probabilities of the future, and he who owns one will be envied by the large landed proprietor and his daughters will be asking "who landed him?"

IMPORTANT BUT NEGLECTED PLANTS

"The Opuntias are very important and much neglected fruiting plants."

DAVID G. FAIRCHILD, U.S. Government Plant Explorer.

CHARACTERISTIC OPUNTIAS

[From Forest and Stream]

"There are many species of the Opuntia in Mexico, not less than a hundred, I should think. Some of these have almost no spines on the leaves. (It is by taking advantage of some extreme form like this that Burbank has produced the spineless cactus.) Others have the tufts of spines so far apart that a goat or a deer may insert his muzzle between and get a good bite, though a cow could not. Others have soft spines, especially when the leaf is new.

There are other very large cactuses -those, for example, known as the saguaro, the pitahaya and the sina, which do not provide good drinking water because their juice is very bitter and even nauseating; and it is interesting to note that these cacti, so unpleasant to the taste, are but slightly protected by the spines, while on the other hand the visnaga and their agreeable tasting allies possess an almost impenetrable armor of hooked and rigid spines."

BURBANK CACTUS IS A GOOD FODDER

From The Berkeley (California) Independent]

Berkeley, February 8- Experiments just completed by M. E. Jaffa, head of the department of nutrition and foods at the University, show that the new species of thornless cactus has properties as fodder for cattle which will equal many of the desert grasses. The tests were made at the request of Luther Burbank, the originator of the new species of plant, and have proved to the full the great importance of the new plant as a fodder for cattle in the wastelands. Professor Jaffa's report on the experiment has just been completed, and will be forwarded to Burbank in a few days.

A short time ago five species of the plant were sent to the agricultural station here to determine the food value. The series of experiments carried on by Professor Jaffa show that the new plant carries nutritive powers which equal three-quarters of that of alfalfa.

SUCCESS DUE TO THE WILD OPUNTIAS

[From Bulletin No. 74, U.S. Bureau Animal Industry]

"It is owing to the existence of the prickly pear that the success of the rancher in southern Texas is largely due. He has in this crop a feed which does not deteriorate if not used for three or even ten years; it is as good at one time as another and can be fed by him in a couple of days notice under any circumstances, although it is the general belief that it is much more valuable in winter than in summer."

"As nearly as can be estimated eighty acres of good prickly pear has furnished a full ration for an average of eight hundred head of cattle for a period of six months."

"Hogs fatten very rapidly on cactus but the spines must be carefully removed."

"No manner of feeding cactus yet devised, without greater care than the feeder is usually willing to bestow upon the work, does away entirely with the evil effects of the spines."

* Manual of Algerian Agriculture, p. 219, reprinted in jour-nal d'Agriculture Tropicale, 1902, p. 331, Riviere et Lecq.

tGrandeau "The Cactus without Thorns," in Nos. 15-20 of Le Temps, September, 1903.

yPaul Bourde "Proposed Inquiry upon the Cactus as a Stock Food." Revue de Tunis, 1894, p. 54.

zThis was accomplished on my grounds several years ago, but there is still room for improvement.

Index | Aggie Horticulture